By Renée Gordon

History & Travel Writer

Paleo-Indians lived in the region as early as 10,000 B.C. The Susquehannock migrated into the area and established palisaded settlements along the Susquehanna River, the largest non-navigable river in the country. They farmed, fished and hunted in what is now Baltimore County, but they were primarily traders. The trails they used for trade would later become wagon roads and then routes we continue to use today. #visitHarford

First contact was made with John Smith in 1608 when he sailed up the Susquehanna. He encountered the “people of the muddy river.” There were believed to have been more than 6,000 natives in 1608, only 300 by 1700 and In 1763 the remaining 30 were slain by settlers in nearby PA. The Indians signed a treaty in 1652 that essentially ceded all of their land.

The 33-mile Lower Susquehanna Scenic Byway journeys through Havre de Grace to U.S. 1 and ends in Perryville. The byway provides glimpses of what the early inhabitants would have seen as well as  Piedmont Forests and the 1928 Conowingo Dam. It is the second largest hydroelectric project in the country. www.visitmaryland.org/scenic-byways/lower-susquehanna.

Piedmont Forests and the 1928 Conowingo Dam. It is the second largest hydroelectric project in the country. www.visitmaryland.org/scenic-byways/lower-susquehanna.

Godfrey Harmer gained a 200-acre plot of land, Harmer’s Corner, in 1658. The plot would later become Havre de Grace’s Historic District. When, in 1695, a ferry service was instituted and was renamed Susquehanna Lower Ferry. The ferry would prove invaluable during the American Revolution and the Civil War as a crucial means of troop transport.

The eastern portion of Baltimore County was taken to form Harford County in 1773. It was named in honor of Henry Harford, Maryland’s final the final proprietor. The county seat, Old Harfordtown, was situated on the Bush River. After several name changes it was named Bel Air.

Havre de Grace was officially founded in 1782, the second oldest municipality in the state. It received its name from General Marquis de Lafayette. While traveling to Philadelphia Lafayette reached the juncture of the Chesapeake and Susquehanna and declared that it resembled Le Havre, a French port. Robert Stokes based the city’s grid pattern on Philadelphia with Revolutionary and French named streets.

The complete Havre de Grace Historic District downtown was listed in 1987 on the National Register of Historic Places in 1987. The Concord Point Lighthouse complex was added in 1976. The architectural styles are representative of the 18th to 20th centuries.

The Havre de Grace Promenade is a scenic ¾-mile walkway that winds along the river. As you meander you have access to Informational signs that interpret the area’s history and thematic sculptures. The Concord Point Lighthouse is a significant attraction. It is 36-ft. tall, has a 31-inch base and was erected of granite on the bay in 1827. Originally the light consisted of 9 oil lamps. It was automated in 1920 and decommisioned in 1975. A historic lighthouse keeper’s cottage is located nearby.

The 8-acre Millard Tydings Park, adjacent to the Promenade, is the site of Ernest Burke’s Memorial Statue. Burke pitched in the Negro Professional League 1947-49. An orphan, he served in the Marine Corp in WWII achieving the Rifle Sharpshooter Ribbon Bar and the WWII Victory Medal. Later in life he became a motivational speaker.

Liriodendron Mansion was constructed in 1898 as a summer residence for Dr. Howard Kelly in Palladian style. He was a founder of Johns Hopkins Hospital and Medical School. The mansion is listed on the National Register. The site includes original furniture, a small museum, art exhibits, parklands and expansive gardens. Tours can be scheduled. liriodendron.com

Havre de Grace is the “Decoy Capital of the World” and the 1986 Havre de Grace Decoy Museum honors, preserves and showcases the tradition. The collection includes both decorative and utilitarian decoys and the 2-level museum tour begins with Native American models. Step out onto the terrace on the second level for outstanding views. Visitors can also watch carvers at work. decoymuseum.com

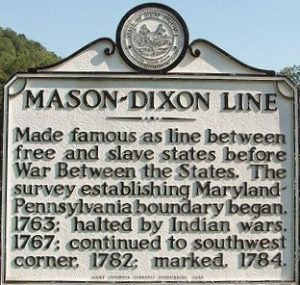

Maryland was a slave state but it witnessed a 37% lowering of numbers between 1750 and 1865 and that is reflected in the numbers holding anti-slavery beliefs. Harford County is on the Mason-Dixon Line that separated slave and free states as stated in the controversial 1820 Missouri Compromise. Location and access to water routes put Harford County at the heart of Underground Railroad activity.

Maryland was a slave state but it witnessed a 37% lowering of numbers between 1750 and 1865 and that is reflected in the numbers holding anti-slavery beliefs. Harford County is on the Mason-Dixon Line that separated slave and free states as stated in the controversial 1820 Missouri Compromise. Location and access to water routes put Harford County at the heart of Underground Railroad activity.

Havre de Grace Maritime Museum has mounted a phenomenal new exhibit, “Underground Railroad, Other Voices of Freedom,” designated a National Underground Network to Freedom site. The 600-ft. gallery is interactive and weaves photographs, original art, documents and first-person narratives together to relate compelling stories of escape on the Chesapeake and the Susquehannah. This is a unique and important story. Additional galleries feature maritime and Native American history. www.hdgmaritimemuseum.org

The 1808 Hays-Heighe House is located in Bel Air and gains its significance from being mentioned in William Still’s book, The Underground Railroad. “Sam,” an enslaved man belonging to Thomas Hays, escaped in 1860. Still documented his story once he reached freedom.

Ladew Topiary Gardens is one of the “10 incredible topiary gardens around the world.” In 1929 Harvey LaDew purchased 250-acres and the gardens were created in 1930. There are 22-acres of formal gardens, more than 90 topiaries, 5 garden rooms, a fountain and nooks and crannies for scenic contemplation. Highlights of the gardens are a 96-year-old swan hedge, the topiary Hunt Scene and LaDew’s mansion. www.ladewgardens.com

The Pulaski Highway was a 62-mile section of Route 40, along the New York to Washington corridor. During the Depression it was a through road to San Francisco and the “Fastest Route West.” Maryland law stated that black passengers had to move to a colored car when entering the state on public transportation. Elkton, MD was the northern station used to make the exchange. There were challenges to the law regarding transportation but those in private vehicles simply were denied service along Route 40.

The ambassador from Chad was going to Washington in June of 1961. He stopped his limousine at a diner for coffee and was subject to racial slurs and made to leave. The incident made international news and other ambassadors reported similar treatment. President Kennedy was called upon to respond and the federal government began to take notice but the changes were not for African Americans.

CORE organized picketing and Freedom Rides along 40. A Freedom Ride took place on December 16, 1961, after many motels and restaurants refused to desegregate, leading to more than 70 arrests. Those arrested were sent to jails or mental institutes. The Freedom Rides led to Maryland’s 1963 Public Accommodations law, barring racial discrimination. On November 14, 1963, Kennedy dedicated a limited-access highway that would become Interstate 95. Freedom Ride on Route 40 Tour can be reserved at harfordcivilrights.org/tours

Spring Hill Suites in Belcamp offers perfect accommodations for a visit. It is centrally located and provides all amenities.

Extended Weekend Getaways

Extended Weekend Getaways